The Fogg Behavior Model (or ‘behaviour’ for those of us on this side of the pond) helps us to tackle the biggest challenge in L&D: transforming learning into action.

Knowledge is power, but only if it’s applied. Otherwise, it’s just theory collecting dust. Yet, the idea of changing behavior often feels intimidating. It might seem more like magic than the work of a learning designer.

However, as BJ Fogg himself says, ‘Behavior and behavior change is not as complicated as most people think. It’s systematic.’ And if it’s systematic, that means we can map it, model it, and master it.

In this article, we’ll break down the Fogg Behavior Model, its three core elements (plus key sub-elements), and show you how to apply it to your learning programmes for real-world impact.

Ready to turn theory into action? Let’s start!

Who is BJ Fogg?

Brian Jeffrey “BJ” Fogg (born August 1963) is an American behavioral scientist, author, and Stanford University professor. He’s also the founder and director of the Stanford Behavior Design Lab, where he researches how technology and psychology influence human behavior.

For over 25 years, BJ Fogg has been at the forefront of understanding how behavior change really works. He packed all that wisdom into Tiny Habits (2020), a practical (and surprisingly fun) guide to building habits that actually stick.

He’s probably best known for his work on behavioral frameworks, including the Fogg Behavior Model, which we’ll be focusing on in this article.

What is the Fogg Behavior Model?

Formally introduced in 2007, the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM), is a framework that explains what causes behavior change.

The model emerged from years of observing patterns in human behavior, synthesising findings from social psychology, and applying these insights to design. BJ also gained useful insights by testing various digital products to see what drove user behavior.

Fogg’s framework states that for a Behavior (B) to occur (such as quitting smoking or completing your compliance training), three elements must converge simultaneously:

- Motivation (M): The desire to perform the behavior.

- Ability (A): How easy it is to perform the behavior.

- Prompt (P): The cue or trigger that initiates the behavior.

We can neatly summarise this as: B = MAP.

Simple, right? Well, there are a few other considerations you need to keep in mind.

- Simultaneous Convergence: All three elements (motivation, ability, and prompt) must be present at the same time for the behavior to occur. In other words, even if someone is highly motivated and capable, the behavior still won’t happen without a prompt.

- Tricky Trade-offs: Motivation and behavior have a compensatory relationship. If someone has high motivation, they may perform a difficult behavior. Likewise, if a behavior is very easy to do, it can occur even with low motivation (provided there’s a clear prompt).

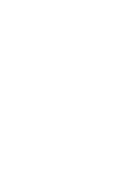

- The Action Line: The model is often visualised on a graph (see above) where the y-axis represents motivation and the x-axis represents ability. Note the action line that curves across the graph. Behaviors above this line are more likely to occur when prompted, while those below are less likely.

The key innovation of the Fogg Behavior Model is how effortlessly it cuts through the complexity of behavior change. While most theories obsess about changing mindsets over time, this model zooms in on the critical moment when someone actually does something. In this sense, it’s remarkably practical and action-oriented.

Although it’s primarily used in designing products and services to encourage specific user behaviors (similar to the Hook Model), it’s also applicable in various other contexts. This includes personal habit formation and the wonderful world of learning and development (L&D).

Understanding Motivation

Though simple, Fogg’s framework does offer nuance by expanding on each key element. For example, he captures the complexity of motivation by categorising it into three ‘Core Motivators’, each with opposing sides:

- Sensation: This refers to our physical experiences. Motivation here stems from our desire to pursue physically pleasurable sensations and skillfully evade physically painful ones. Let’s illustrate this with some examples:

- Pleasure: We eat dessert because it delights our taste buds.

- Pain: We avoid treading on garden rakes because it hurts.

- Anticipation: This involves our emotions about what might happen in the future. As you’d expect, we are motivated by the anticipation of positive experiences and demotivated by the prospect of negative ones. For example:

- Hope: We study because we dream of acing a test.

- Fear: We procrastinate because we dread failing.

- Belonging: This taps into our inherently social nature. We are motivated to do things that make us feel accepted by others and avoid acts that could lead to social disapproval or exclusion. This includes:

- Acceptance: We follow fashion trends to help us fit in.

- Rejection: We skip a party to avoid social anxiety.

And remember, according to Fogg, motivation isn’t a binary ‘on’ or ‘off’ switch. It exists on a continuum from low to high, with varying degrees of influence.

Understanding Ability

The next element in Fogg’s model is ability. He notes that simplifying a behavior is often more effective than boosting motivation. Furthermore, he breaks down ability into six subcategories that influence how easy it is to act.

- Time: Time is a precious resource and nobody wants to waste it. As a result, the less time it takes to complete an action, the more likely we are to do it. For example, reading a summary is considerably easier than reading a full report.

- Money: Unless you’re Bruce Wayne, you probably track how much you spend and on what. More expensive behaviors generally necessitate higher levels of motivation. For example, downloading a free tip sheet is easier than purchasing a $100 course.

- Physical Effort: Physically demanding actions can be draining. We typically avoid this kind of effort unless there’s a clear payoff, like an endorphin rush or achieving our fitness goals. For example, a ten-minute walk is easier than completing a 10km run.

- Mental Effort: Focused and conscious thinking makes us tired and requires effort. As a result, you’re more likely to complete an action if it’s not mentally taxing. For example, reading an airport thriller is easier than deciphering the complexities of Finnegans Wake.

- Social Deviance: We don’t like to go against the grain. This is why it’s difficult for us to perform behaviors that clash with established social norms. For instance, agreeing with the group is often easier than voicing a potentially controversial opinion.

- Non-Routine: Established daily routines provide a framework for our lives. Actions that deviate from these routines face a higher barrier to completion. For instance, shifting your gym visit from morning to evening is generally harder than maintaining your usual time.

Understanding Prompts

The final element of Fogg’s model is prompts, also known as triggers. These are the cues or calls to action that initiate behavior. Fogg identifies three different categories of prompts depending on where someone falls on the motivation and ability spectrum.

- Spark: This type of prompt is most effective when someone has high ability but low motivation. It’s the ‘spark’ that ignites their desire to take action. For example, receiving an urgency-generating ‘Only 2 left in stock!’ notification about a product on your wishlist.

- Facilitator: Conversely, this prompt works best when someone has high motivation, but low ability. It should seek to make the behavior easier to do. Examples include sending pre-filled patient forms prior to an appointment and the ability to use a saved card when making an online purchase.

- Signal: This final prompt type is effective when someone has high motivation and high ability. It provides a gentle nudge that encourages a behavior the person already wants to do. For instance, this could be a calendar reminder or push notification.

Of course, all this means that timing is essential. The prompt needs to occur when the person has the relevant level of motivation and ability, and it should be designed to connect with their current desires.

Why the Fogg Model is Relevant for L&D

As L&D professionals, we’ve seen it all. A shiny new training programme gets rolled out, everyone completes it… and nothing changes. People go right back to doing things the old way (or the easy way). All those hours spent designing content were for nothing.

This is precisely what makes Fogg’s model a valuable tool for learning pros. It offers a clear framework to understand why certain new skills and knowledge are adopted and applied by learners, while others are not.

It also arms us with a clear structure for designing more effective learning experiences (more on this shortly). After all, by understanding how motivation, ability, and prompts drive behavior change, you can refine your training programmes accordingly.

Still need convincing? Research suggests that the Fogg Behavioral Model can be effective in a variety of contexts:

- A 2021 study demonstrated that when Fogg’s model was applied to a waste-reduction app, users completed 94.3% of tasks. This was a significant increase in engagement.

- Similarly, a 2022 study highlighted the model’s adaptability in low-resource settings, where it successfully improved health-related behaviors such as vaccine uptake and contraceptive usage.

- This 2025 study found that participants trained in cybersecurity skills using the Fogg Behavioral Model were 2.65x more likely to adopt recommended security practices.

And finally, Fogg’s framework encourages a healthy focus on actionable outcomes. We all know that it’s too easy to fixate on knowledge acquisition. However, this model pushes us towards applying and utilising what’s been learned, aligning with the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Applying the Fogg Model in L&D Practice

Thankfully, the Fogg Behavior Model isn’t just a theoretical framework. It also provides practical guidance for designing more effective and engaging learning experiences that lead to real behavior change. With this in mind, let’s explore how you can apply each element of the model.

1. Make it Easy (Ability)

As we’ve already seen, one of the most effective ways to encourage a new behavior (like completing a training programme) is to make it easier to do. If your training requires heroic effort to apply, it just won’t stick. So, it’s up to you to bury the friction.

Our first recommendation is to use microlearning (or even nanolearning). By breaking down complex information into smaller, easily digestible chunks, you reduce cognitive load. For example, instead of a one-hour webinar, why not offer a series of 5-minute video tutorials?

You should also ensure your resources are easily accessible precisely when and where your learners need them. This reduces the time and effort learners spend searching for information. Additionally, don’t forget to provide clear and unambiguous instructions for each activity.

2. Increase Uptake (Motivation)

While making things easier is often the most direct route to behavior change, tapping into learners’ motivations can also be powerful. As we know, this requires a delicate balance of pleasure, pain, hope, fear, acceptance, and rejection.

This can often be achieved through gamification. For example, why not use game mechanics like experience points, badges, and leaderboards throughout your training programme? This offers learners both immediate feedback and recognition.

Next, try to situate your learning within a social environment. Encourage collaborative learning, peer feedback, and opportunities for learners to share their knowledge. Fortunately, many learning management systems offer social learning features to facilitate this.

3. Effective Triggers (Prompts)

Of course, even with high motivation and ability, learning won’t translate to behavior change without a prompt. As such, you should strategically consider how to cue learners to apply their new knowledge and skills. Here’s an example for each prompt type to get you started.

- Spark Prompts: Need a call to action that ignites motivation? Try sharing success stories from peers who have previously applied the learning. These case studies clearly illustrate the ‘what’s in it for me?’ for your learners, making them more likely to act.

- Facilitator Prompts: Need a cue that makes activity easier? Ensure you provide direct links to any relevant resources and easy access to your learning platform. Embedding job aids directly within employees’ workflows is also crucial.

- Signal Prompts: Need a simple reminder to take action? There are several approaches you can take. For example, you could implement recurring calendar reminders or push notifications that help to propel your learners in the right direction.

The Limitations of the Fogg Behavior Model

While the Fogg Behavior Model offers a brilliantly practical framework for understanding and influencing behavior, it’s not without its limitations. Indeed, this model (and others like it) has faced its fair share of critiques.

Firstly, there’s the thorny issue of human motivation, which isn’t as easy to break down and categorise as we might like. While Fogg’s model gives it a good shot, factors like intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and personal and cultural values might not be fully captured.

The fact that so many motivation models exist shows just how complicated it is:

Fogg’s framework also primarily focuses on the here and now, which has both advantages and disadvantages. For instance, it’s less comprehensive for understanding and sustaining long-term behavior change, which typically requires deeper shifts in motivation and habit formation.

Finally, like other behavior design models, Fogg’s framework raises ethical concerns about potential manipulation if user well-being isn’t prioritised. These concerns are amplified in a world saturated with persuasive technology and aggressive marketing strategies.

Ultimately, it’s up to you to ensure you have your learners’ best interests at heart. Ask yourself this: am I making their lives better, or just checking a box?

Final Words

So, there you have it. The Fogg Behavioral Model is your blueprint for turning learning into lasting change. By focusing on motivation, ability, and prompts, you’re not just designing training, you’re engineering behaviors that stick.

Don’t forget, one of Fogg’s key insights is that it’s often more effective to focus on ability rather than motivation. Instead of burning energy trying to ‘pump up’ your learners, why not focus on removing friction?

With this understanding, you can now start planning which learner behavior you’ll redesign next. Whether focusing on cybersecurity, sustainability, or compliance, remember that small, strategic adjustments can create big shifts. Good luck!

Thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this content, please connect with me here or find more articles here.

You’ve started strong with the Fogg Behavioral Model. Now, expand your knowledge with our new guidebook, ‘The Learning Theories & Models You Need to Know’, for a complete overview of the essential learning theories and models.