We’ve all written them. Those obligatory ‘At the end of this course, learners will be able to…’ statements that everyone forgets five minutes later. But what if we told you that far from being a formality, learning objectives are the single most powerful tool for ensuring learning success?

Too many learning programmes fail because they’re built on a weak foundation. Without precise objectives, training becomes a watered-down time vacuum that’s expensive, forgettable, and disconnected from real business results. At this stage, you’re effectively throwing spaghetti at the wall.

In this article, we’ll show you how to fix that. We’ll detail the anatomy of a good learning objective, provide a step-by-step guide to writing them, and highlight the common pitfalls that learning designers often encounter.

Put differently, by the end of this article, readers will be able to create learning objectives that truly engage their learners and produce meaningful organisational impact. But first, let’s start with a definition.

What is a Learning Objective?

Simply put, a learning objective is a target for the mind. It’s a clear, action-oriented statement that defines exactly what a learner will know or be able to do by the end of a course or lesson. It helps to make success measurable and unambiguous.

It’s the difference between a casual stroll and a purposeful journey. An aimless walk might be relaxing, but you can’t measure its success because you never had a destination in mind. Indeed, this destination is useful both for the learner and the learning designer:

- The Learner: Learning objectives tell learners exactly what is expected of them and what they will gain from the experience. This helps to focus their attention and can even increase their motivation.

- The Designer: Instructional designers need clear objectives so they can determine which content to include, which instructional strategies to use, and what assessment methods to deploy.

Learning objectives are at the heart of curriculum development at all levels. In self-paced online courses, learning objectives are used to chunk content into manageable, goal-oriented modules. They provide learners with a clear pathway through the material.

Note: Learning objectives are often confused with learning outcomes, but they’re different beasts entirely. The distinction lies in the timing and scope. An objective is about what the learner masters within the course. An outcome is the larger change that happens because of the course.

The Anatomy of a Good Learning Objective

Now we know the role learning objectives play, the next step is to understand their core components. After all, a well-constructed objective isn’t a vague statement of intent; it’s more like a precise blueprint for learning behaviour. And precision requires structure.

The most widely used framework for this comes from American psychologist Robert Mager (1923-2020). In his 1962 book, Preparing objectives for programmed instruction (later updated to the more snappy titled Preparing Instructional Objectives), he identified three key ingredients:

1. Performance (The Action)

First up, any learning objective worth its salt needs a measurable verb that describes what the learner will do. In turn, this forces learners to think about the tangible, on-the-job behavior change that will result from their learning experience. Strong verbs should be used to drive activity:

- Weak Verb Example: Learners will understand the function of a coffee machine.

- Strong Verb Example: Learners will be able to brew a perfect cup of coffee using the office coffee machine.

Note the shift from the wishy-washy ‘understand’ to a measurable action like ‘brew’ — although you may quibble over what constitutes a perfect cup of coffee.

2. Condition (The Context)

Next up, we need to specify the circumstances under which the learner will perform the action. Here you’re seeking to understand the limitations they’ll be working under, and the tools and resources they’ll have available. This helps to keep things realistic and grounded.

- Example without a Condition: Learners will be able to bake a batch of cookies.

- Example with a Condition: Learners will be able to bake a batch of cookies using an oven and ingredients found in a standard kitchen.

3. Criterion (The Standard)

Finally, a criterion helps to establish the standard of acceptable performance. It enables the learner to understand what success looks like. This element is what makes your learning objectives truly measurable and allows you to design an accurate assessment.

- Example without a Criterion: Learners will be able to make a pizza.

- Example with a Criterion: Learners will be able to make a pizza that is rated ‘delicious’ by at least three other people.

The criterion itself can be a qualitative measure (for example, an accuracy percentage, sales target, reduced number of errors, etc.) or a qualitative one (adheres to company policy, aligns with brand guidelines, exceeds manager expectations, etc.).

Bringing it All Together

With all three ingredients in place, you’ll now have a clear goal, with a measurable outcome that makes sense within your specific context. This is what transforms a simple statement into a meaningful and powerful objective. Consider the following example:

- Weak Objective: Learners will know how to take care of a houseplant.

- Mager Objective: Learners will be able to follow the provided watering and feeding schedule for a houseplant for four consecutive weeks.

As Mager himself puts it, ‘Objectives must be clear, concise, and learner-focused’. You should keep this guiding principle in mind as you combine your performance verb, condition, and criterion.

Addendum: SMART Goals

To ensure your learning objectives are practical and effective, you may want to complement Mager’s principles with SMART criteria. While they’re typically the language of business strategy, they can help to refine your focus.

According to this handy acronym, goals should be:

- Specific: Your objectives should be clear and unambiguous.

- Measurable: Learners should be able to track their progress.

- Achievable: The objective should be realistic for the target audience.

- Relevant: Behavior change should be linked to broader goals.

- Time-bound: All objectives need a deadline to generate urgency.

Certain elements of the SMART criteria aren’t explicitly mentioned in Mager’s approach (relevancy, time sensitivity, and arguably, achievability). As such, they are worth considering when formatting your objectives.

The Benefits of Good Learning Objectives

Though an old-school technique, the power of sharing learning objectives is backed by a solid body of evidence that confirms their profound impact on both learners and designers. In short, they are a critical tool for success. Here’s why:

- Efficient Design: Creating instructional content isn’t easy, so you don’t want to waste time on unnecessary or peripheral materials. Thankfully, by starting with objectives, you can use a process called ‘backward design’. This method saves time and effort by focusing only on the essential activities needed to achieve the programme’s goals.

- Clear Expectations: Learning objectives tell learners exactly what’s expected of them and what they’ll gain from the experience. As this 2017 study puts it, ‘Learning objectives also contribute to shaping expectations, preparing learners for the educational activity and the standard by which their performance will be measured’.

- Better Focus: These expectations help learners to train their focus on the activities that matter most. This ensures their efforts are tightly aligned with your programme’s intended outcome. Indeed, according to this study, 74% of learners agree that learning objectives have a positive or neutral impact on their ability to focus.

- Accountability & Alignment: Clear objectives establish a shared understanding of success, which drives accountability for both the learner and the learning designer. In fact, as this study shows, learners regularly adjust their approach to learning in line with their prescribed objectives.

- Improved Outcomes: Of course, all this extra effort matters very little if it doesn’t improve learning outcomes. Luckily, according to this 2017 study, learning objectives help students to ‘better understand course activities and increase student performance on assessments’. This makes them essential as part of any learning programme.

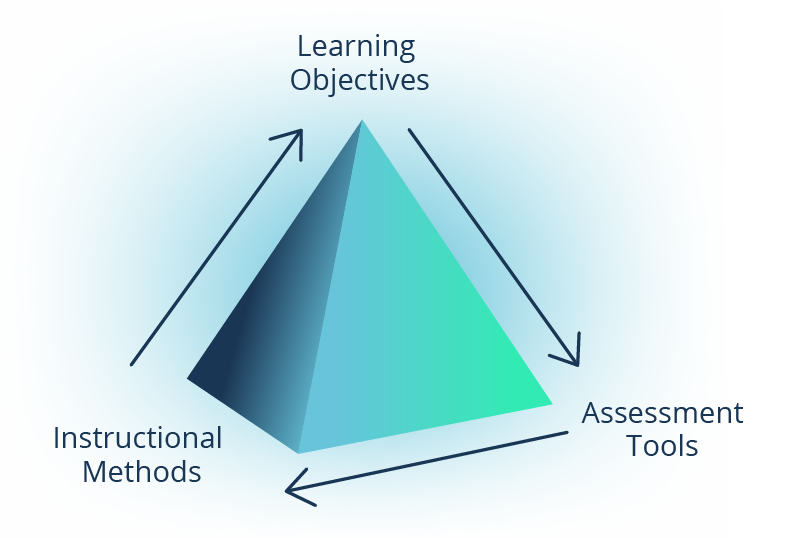

Still not convinced? Consider the ‘Golden Triangle’ of instructional design. This model suggests that learning objectives are the foundation for instructional alignment. They are the central point that connects the three key components of any given learning experience:

- Learning Objectives (The What)

- Instructional Methods (The How)

- Assessment Tools (The How Well)

This alignment ensures that every element of your learning programme serves the same clear purpose. And the clearer you can make it (and the more meaningful), the easier it will be for your learners.

How to Create Learning Objectives

Now we know why it’s so important to get our learning objectives right. Thankfully, this can be achieved through a simple step-by-step process. To help light your way, this guide will walk you through the key considerations for building effective objectives:

Step 1: Work Backwards

Before you do anything else, you need to identify your desired performance outcome. In other words, what specific, observable behavior do you want your learners to demonstrate as a result of this training? You’ll then be able to work backwards from that starting point.

If you don’t have a specific goal in mind, you should begin with a training needs analysis. This will help you to identify performance gaps and define specific objectives that are directly tied to your organisation’s business goals.

Hint: A great starting point is to complete this phrase: ‘At the end of this learning experience, the learner will be able to…’

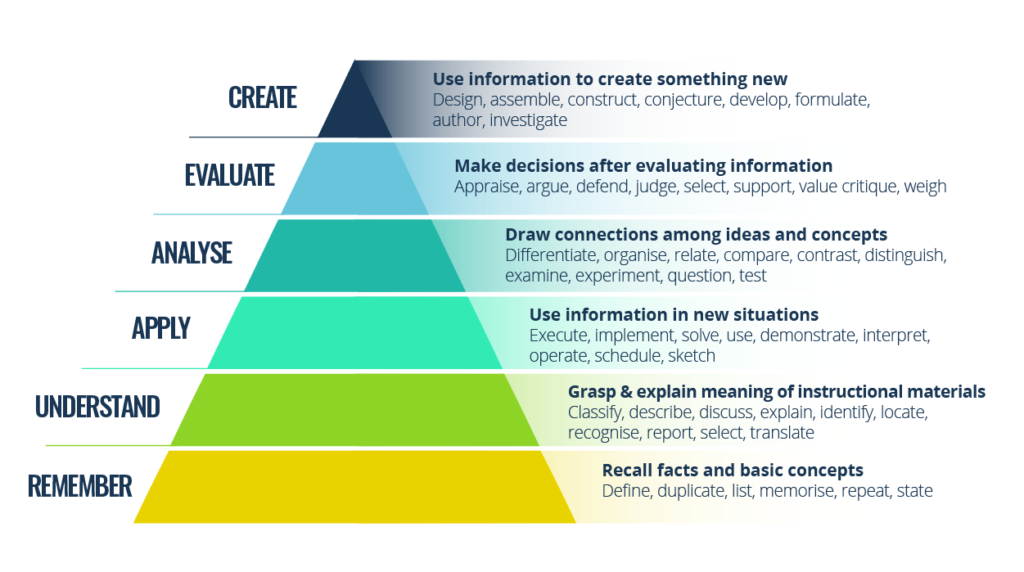

Step 2: Come into Bloom

With a behavior in mind, you can now use Bloom’s Taxonomy to recruit the perfect action verb for your cause. Bloom classifies cognitive skills into a hierarchy, from simple recall to complex creation. This also ensures that your objective is set at the right level of difficulty.

You can see the full range below, alongside some example action verbs.

Step 3: Mager Mode

Now it’s time to get more specific. Think back to Robert Mager’s model, as detailed above. So far, we’ve established the performance verb, but we are missing the condition and the criterion. You can establish these important elements as follows:

- Condition: Ground your objective in reality by considering the tools and resources your learners have available to them. Your objective should be as relevant as possible to your learners’ actual work environment.

- Criterion: Next, help to set the bar for success by making your objective measurable. You can use quantitative or qualitative measures, as long as it’s possible for learners and instructors to assess results accurately.

Step 4: Review & Refine

By combining your performance verb, condition, and criterion, you should now have a clear written objective. It should be specific and unambiguous. However, before you finalise it, consider testing it with your colleagues or a small group of learners.

Their feedback can help you to validate its clarity. If everyone is aligned and happy, then you now have a foundation for your entire learning programme. Congratulations!

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even with our strong framework in place, it’s still all too easy to fall into common traps when writing learning objectives. We’ve outlined these pitfalls below, so you know exactly what to guard against.

- Vanquish Vague Verbs: Remember that objectives focus on observable actions, not internal thought processes. Banish words like ‘understand’, ‘know’, ‘learn’, and ‘appreciate’ from your writing process. Instead, focus on strong action verbs that identify the specific behaviors learners can perform to demonstrate their knowledge.

- Don’t Get Topical: A common error is to write an objective that is actually a topic or a list of content. For example: ‘The History of eLearning’ is a subject, not a clear goal. The key difference is that a topic is what you teach, while an objective is what the learner will be able to do with what they’ve learned.

- Don’t Drown Your Learners: When designing a course or a module, there’s always a nagging temptation to list every single thing the learner will do. Unfortunately, this usually leads to a long, unwieldy list of objectives that overwhelms both the learner and the designer. Keep it as simple as possible.

- Don’t Skip The Assessment: If you can’t design a test, an activity, or an observation to measure an objective, then it’s not a good objective. To achieve this, each objective must focus on a measurable behavior. If this is not currently the case, then you’ll likely need to return to point one and replace any vague verbs with better terms.

Similarly, you can’t just set an objective and consider the job done. You need to track your progress over time and monitor performance. You may also need to update your objectives (and subsequently your content and assessments) as your organisational goals evolve over time.

Linking Objectives to Wider Goals

Steering clear of these pitfalls will set you on the path to success. But before setting off, ask yourself: what’s your ultimate destination? After all, the true purpose of corporate learning isn’t just to know more, but to do better.

Your learning objectives are the crucial link between theory and results. When you tether them to specific performance outcomes, you transform training from an abstract exercise into a powerful driver of organisational goals.

This is also a good opportunity to showcase concrete financial value. For example, if you set an objective to ‘reduce data entry errors by 10%’, you can then use this figure to calculate the financial savings that will result. In turn, you’ll be able to show a direct ROI from your training investment.

Instead of seeing objectives as a compliance checkbox, you should utilise them as the strategic tool they are designed to be. By doing so, you’ll start making a real impact on your business and prove your value at lightning speed.

Final Words

Creating powerful learning objectives isn’t an administrative task — it’s a key part of the learning design process. Doing this translates organisational goals into a clear path for employee growth and performance improvement.

Mastering this skill requires combining three key elements: a performance verb, a condition, and a criterion. You should also take care to keep things clear and unambiguous, so it’s easy for your learners to understand.

In turn, the objectives you write today will be the business results you’ll report tomorrow. This will empower you to build both better training and a more impactful and successful organisation. And if that isn’t an objective worth chasing, then we don’t know what is!

Thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this content, please connect with me here or find more articles here.

Learning objectives are the crucial first step, but they’re just one part of the instructional design journey. For a complete, end-to-end guide to creating engaging learning experiences, download ‘The Ultimate Instructional Design Guidebook’ now!